Why I Love TCL

"The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated"

Mark Twain didn't have the luxury of having a favorite programming language, having lived before the computer revolution. Were he alive today, one could reasonably imagine him having a closet full of arcane computers that he would show and tell to anyone that happened near. If he also wrote code as a hobby, I think he'd probably use TCL. TCL is the dead language that won't die... slammed by "real programmers" for most of its existence and now relegated to the oddball corner of half-dead ways to talk to a computer. It has also been my language of choice for more than 20 years, and I have used it personally and professionally to do cool things with computers and to have a lot of fun.

At a time when AI-driven "vibe" coding advocates pursue the extinction of human programmers, now is as good a time as any to write about this wonderful language and the larger idea that programming is a worthwhile end in itself, and that programming should be accessible to anyone that wants to try it. The modern computer user has been conditioned to be a passive consumer, at the whim of programmers and vendors to determine what they can or cannot do. Convenience and ease have been the carrots, but I fear that digital sovereignty, individual human competence and humanity actually harnessing the true power of computers will all fall to the wrong end of the club. And that would be a shame, even if it is inevitable.

I make no claim to be a professional programmer. I am neither properly disposed or inclined, and my career has taken me in other directions. Nonetheless, I have done some pretty cool things in the real world using TCL, and in most cases using only TCL. These include:

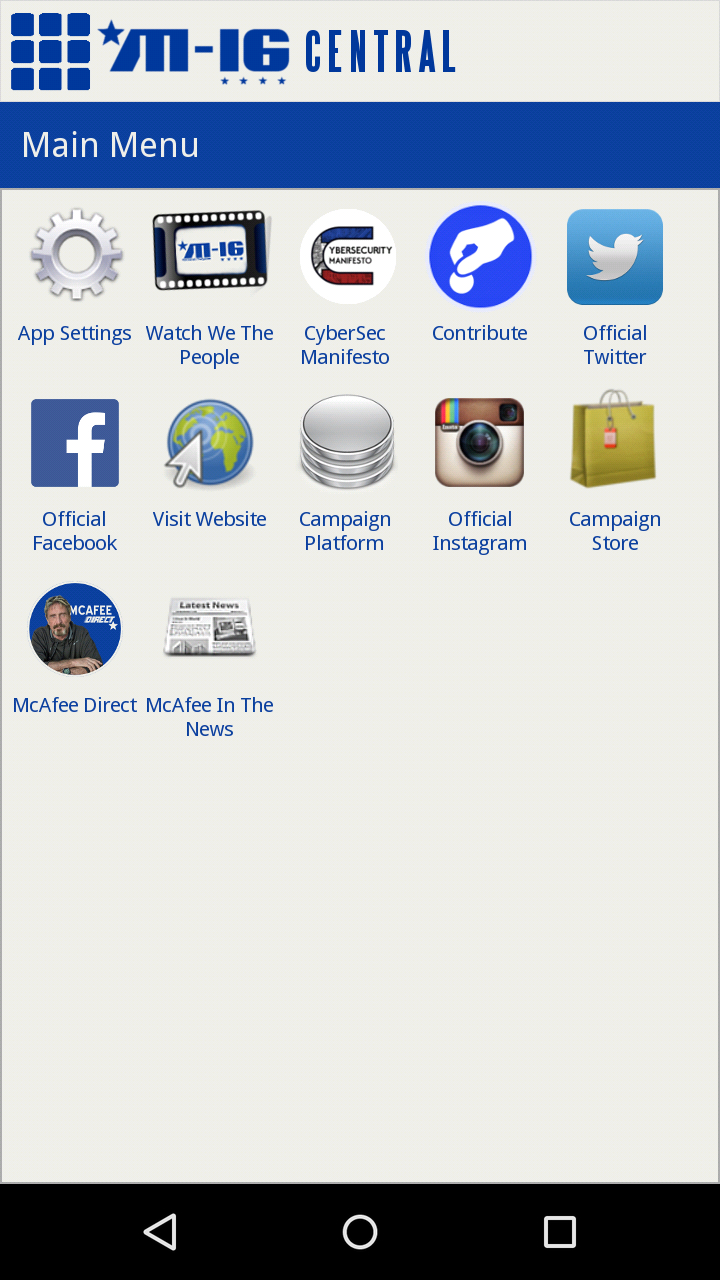

- Support for campaigns by John McAfee, founder of McAfee Antivirus, for President of the United States in 2016 and 2020. TCL code managed many of our lists, automated data collection, and was used in graphic design, printing and video production for the campaign. I also built an Android campaign app in 2016 that used TCL under the hood (using Androwish) to help users to keep up with the campaign.

- A fully automated product scanning solution that helped a fairly large company to prove a multi-million dollar ongoing theft by a vendor.

- My 2 year run of Crypto Degenerates with the incomparable Darko from Crypto Tonight used TCL to produce most of the episodes. Production of the final product, with credits and cuts, was fully automated from a single take of raw video using TCL and FFMPEG. All I had to do was show up.

- Several smaller projects used in various business roles to solve problems like product sorting, data reporting and team management.

In addition to these real world applications, I've usually had a hobby project active on the side. Some of the cooler thing I've managed to build include:

- A custom desktop environment and window manager for X11/Linux

- A display toolkit that uses the Linux framebuffer directly for rendering

- A GLSL framework that uses the TCL3d package to run fragment shaders with uniform support and dynamic textures

- An emulation layer for GLSL, called TLSL, that allows modified GLSL fragment shaders to run without OpenGL using threads

My point in sharing these lists is not to blow my own horn, but to demonstrate what is possible using TCL. The fact that TCL allowed someone that can't stand doing math and can't stand excessive rules to actually get things done on a computer is something of a minor miracle, so much of the credit really should go to John Ousterhout, inventor of the TCL language.

There have been times that TCL didn't support something I wanted to do easily or reliably. Either the libraries just weren't there, or lower level access to the underlying operating system was needed. The result was me learning enough about a new language to at least be able to use it to modify existing code. In this way I learned a little about Perl, Python, JavaScript, Java, and C. While many people are very successful using these more popular languages, if I had tried completing any of my larger projects in any of them I probably would have stopped. It would have been far less fun, far more aggravating, and generally not worth it.

One big attraction to TCL for me stems from the fact that I've never really liked rules. I understand the utility of rules, and why some rules are necessary in most circumstances. But I don't agree that we need lots of rules, or that having lots of rules makes things better. That's a debate for another day, but suffice it to say that in programming languages, lots of rules is the norm. And as with other things, some of it is understandable. In programming, having some well defined rules is essential in order that the computer can understand our human abstractions and do what we want. Some rules help other programmers understand your code better, like the draconian whitespace rules of Python. That is all fine and large, but really not a problem that I care about for my personal projects. So why should I worry about those rules, especially when the liberal use of whitespace often helps me to conceptualize what I'm trying to do and allows me to work faster?

While there are languages with even less rules than TCL, I don't think any of them are very practical languages. TCL strikes the perfect balance - 12 immutable rules that govern how the interpreter works. That's all. If I want to store a number, use it as a non-numeric string in a window title, and then use it for math as a number again, I can do that. If I want to arrange my code blocks differently than other programmers, I can do that. The rules that govern syntax are so few, and so clear, that learning them all can be accomplished in an afternoon. It takes more time than that to understand all of the implications, and it takes even more time and a solid knowledge of the C language to understand all of the things that TCL does behind the scenes to make things easy for the user. But to just sit down and write useful code and have it work, TCL was the fastest bootstrap of all the languages I've used.

In programming and in life, I believe that sometimes you need to color outside the lines. TCL lets you do that. Having completed several large projects using TCL, some that have worked for me for years reliably and flawlessly, I can't agree that complexity implosion is inevitable, as some critics of TCL allege. I much prefer the flexibility when I need it to guardrails meant to save me from a fate that, with some discipline, I can prevent myself. Guardrails in programming should never be mandatory if you ask me, but with the rise of "safe" languages like Rust, it seems that I am in the minority with this preference. TCL does have safety mechanisms, indeed some of the concepts for code safety used in languages like JavaScript were pioneered in the TCL world. But they're optional, not mandatory, and that matters.

Rust and other safe languages may have their place, but if languages like TCL are allowed to die on the vine, something important will be lost. Not every block of code is going to power a nuclear reactor, or handle important data. So not every programmer should be required to work under those constraints. TCL also has its place, and I would argue that it is a larger space than just hobby tinkering. It has been used extensively in the engineering and science industries, and notably in microchip design workflows. In there early days, the development of the Linux kernel was managed using a code management solution written in TCL at the time. You may not know it, but there is a good chance that whatever computer or device you are reading this on has some traces of the TCL legacy hidden in the code that powers it, and might even be using TCL code without you knowing it.

Another thing that makes TCL attractive to me is the fact that I value my time. I don't mind spending time on things, but I also don't like putting more time into something than it warrants. TCL is an interpreted language, and the workflow is fast from writing a change to observing the result. While instant gratification is not always the best thing, when you're hot on a problem the fact that TCL is interpreted can save hours upon hours of dev time. When you're just dabbling, with a limited supply of leisure time available, it can mean the difference between pursuing or dropping a hobby. And in business, when time is money and the world changes fast, the rapid pace that TCL affords is a money saver for anyone that uses it.

One of my projects over the course of the last year has been to work at ironing out kinks and cleaning up some of my code so that I can share it. I've gained a lot by using other people's code, libraries and hard work, though I've always been embarrassed to share because I know much of my code is rough and dirty. My only public contribution to date has been some code to manipulate a now obscure image format, XPM.

Another reason I haven't shared a lot is that I'm sure my cumulative codebase contains plenty of mistakes that would invite ridicule from seasoned programmers. And I don't enjoy ridicule all that much. But I am not a programmer, and it would be unfair to hold me to that standard. I'm just a guy that's written some software. Perhaps that is the best endorsement I can give for TCL. It allowed a guy that was into things like cars, whiskey and writing - and not science or math - to do cool things that I want to do with computers and not just what other programmers and companies think I should be doing. If I can do it, and enjoy the process, anyone can.

There is plenty of information about TCL available on the TCL wiki and the TCL Developers Exchange. Anyone can download an interpreter for multiple platforms and be bossing around their computer in no time at all. I'm writing today because I hope this language never dies. If I can convince at least one person that has never written code to try TCL, it will have been time well spent. So, you... get to it.

Data Security: The (Dismal) State of the Art

July 6, 2016