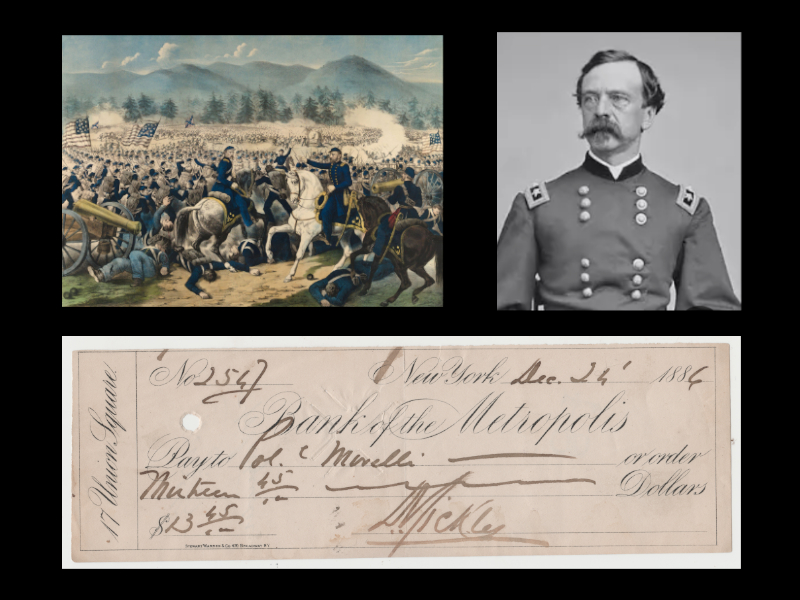

US Government Civil War Cannon Purchase

One of the fascinating qualities of historical documents is the idea that even the most mundane and commonplace examples can hide rich stories and interesting questions within. This Treasury remittance, an auditing tool used to maintain a paper trail on government expenditures, is pretty boring at first glance. Many people, including myself, consider the tracking of money to be one of the least interesting subjects imaginable. Even those that believe the process is an important one usually don't care to examine or hear about the details, only the result.

Yet on reflection, what is being documented here is a bit of an oddball situation with an interesting story, one that tracks with the irregular and unprecedented development of the United States during the 19th century. It brings to light an early American example of some of the questions that surround the advance of technology to this day.

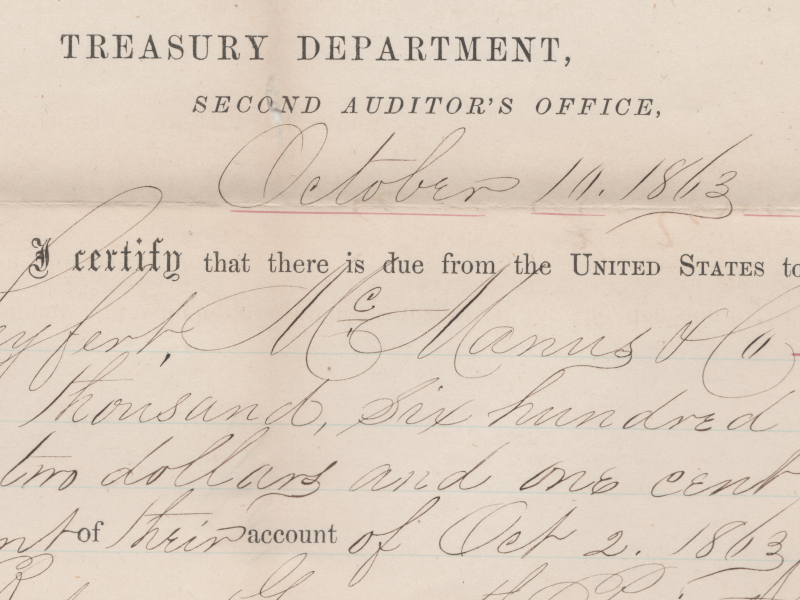

The documented transaction is for the purchase of a cannon and ammunition from the Reading Iron Works in Pennsylvania, which was then owned by the firm called Seyfert, McManus and Co. that is mentioned in the document. The gun would have been cast in the Scott Foundry, built in 1854 expressly for the purpose. The 1863 purchase date places it during the American Civil War, but supporting information makes it unlikely that it was fired during that conflict.

The Rodman Gun was a smoothbore cannon that was cast in barrel sizes ranging from 8 inches to 20 inches. The 10 inch version purchased here would have required a crew of 8-10 men to operate and could fire both solid shot and hollow shell ammunition. The design was named after it's inventor, Thomas Jackson Rodman, who had devised a new casting method called hollow casting that would result in a stronger gun less prone to malfunction or suffer catastrophic failure.

However, there is another type of barrel design called a rifled barrel, which uses grooves in the barrel and matching ammunition to increase both range and accuracy. While the idea of rifling a barrel was not new, the ability to manufacture the guns and required matching ammunition at scale was new to the 19th century, coming as it did with the industrial revolution. Given the obvious advantages a rifled barrel offers, this mass-production capability seems at first glance to spell the end of the utility of the smoothbore design. And for small arms, the ability to mass-produce rifled barrels did indeed herald the future, even though smoothbore small arms still dominated the Civil War arsenal for other reasons.

So this order is a bit of a mystery. From a strictly technological standpoint, a Rodman Gun order on this date is an order for obsolete equipment. The innovations that Rodman's method introduced should have been as relevent as improvements to horse-carriage designs would have been if announced in 1920. Most artillery officers at the time would have prefered a rifled gun to a smoothbore, for all of the advantages the gun offered. If range, accuracy and superior performance under ideal conditions were the only variables, this should be an order for a rifled cannon. Digging into the characters involved, as well as some other less obvious factors sheds light on why this order for a smoothbore cannon was made at this late date.

One of the interesting features of this purchase order is that it contains the names of two Chief of Ordnance officers of the Army, the 5th and 6th respectively. The order was instigated by the 5th Chief of Ordnance, Brigadier General James Wolfe Ripley. But he was sacked from that role on September 15, 1863, about 20 days before the order was made, so this must have been made in his new role as inspector of fortifications for the New England Coast. The order was approved by his replacement as Chief of Ordnance, Brigadier General George D. Ramsay.

James Wolfe Ripley is a name that remains controversial to military enthusiasts and historians. He had very strong opinions about military technology, and as a result made some questionable calls as Chief of Ordnance that are debated to this day. A look at some of those decisions helps to understand why this order was placed despite superior technology being available.

Ripley was promoted to the post of Chief of Ordnance for the Army at the outbreak of the Civil War. He was a career officer who had served in the Seminole War and then worked his way up to Chief of Ordnance of the Pacific Coast Department. Ripley set about his new role energetically and seemed to prefer rifled guns to smoothbores. Impressed by the range and accuracy improvements rifling offered, as well as the introduction of a reliable process to convert smoothbores into rifled guns at scale using machines, he immediately ordered the conversion of older guns that the government already owned to use rifling. So clearly he understood the benefits of rifiled guns, and he wanted those benefits for the Army.

And yet less than 2 years later, his name appears as the originator of a purchase for a smoothbore cannon. Why? That he was a man of strong opinions, there can be no doubt. He was removed from his post after refusing a direct order from President Lincoln to procure breech-loading rifles, another technological advance of the time but one that Ripley was not a fan of at all. Here we begin to see that mere technological superiority was not an inherent good to this man, impressed though he might be with some of the gains.

Breech-loading rifles were a much newer technology than the rifled barrel. The design allows the gun to be loaded much faster than muzzle-loaded guns. There can be no doubt that this design allowed a soldier to maintain a much higher rate of high-accuracy fire than ever before. Even a simple demonstration - and he would have attended many in his role - would have been able to prove this point. They enabled a two brigades of of calvary to hold off most of an advancing Confederate Corp for hours at Gettysburg, and offered similar advantages in every fight in which they were deployed.

Yet there was also no denying the weapon's increased complexity and cost, along with some other tradeoffs. It was not hard to imagine an undisciplined soldier, which the Civil War had a preponderance of compared to more modern conflicts, firing ineffectively as fast as the gun would fire. These were men that would sometimes load multiple shells into a muzzle-loader without ever priming the gun. They'd aim, pull the trigger, and then reload without ever firing. These guns with unfired shells would be found after almost every major engagement, and Ripley could not have been unaware of the problem.

In fact, Ripley was aware of this, and drew reasonable conclusions. Not only did he see the ammunition bill and logistics headaches for the Army going through the roof due to the increased rate of fire, he believed that much of that additional ammunition would have been wasted - fired at nothing by frantic, poorly trained men. Even worse to his mind than the breech-loader were automatically loading guns like the Gatling Gun. These existed at the time, but were hardly used and are generally not associated with that war. Ripley, and the policies of his department, are the reason why.

Frugal? Sure. But not, as some argue, for it's own sake and not because he didn't understand the potential benefits. In a war that saw both Congress and the public howling about the costs the entire time, it is difficult to see how the standard issue of breech-loaders or the mass deployment of Gatling Guns would have been sustained, given the tremendous ramp up in cost that would have resulted. The limited deployment of breech-loaders to elite units of good disipline that could be trained to use the guns properly was actually an intelligent compromise.

To answer the question of deploying rifled small arms instead of smoothbores, Ripley sought to gain the benefits of the technology for the Army without incurring some of the costs. Ordering the conversion of old smoothbore rifles was a key part of his program, even though buying new rifles was not. The government already owned literal tons of smoothbore rifles, he argued, and these could be converted. If Ripley is due valid criticism it is probably here. Yes, the old rifles could be converted, but that takes time while new guns and the ammunition they needed were available right away. What happened is what one would expect, the Army simply deployed what they had on hand, rather than nothing, and most soldiers fought with smoothbores. If Ripley is due criticism for his frugality extending the war, it probably is for this decision.

But heavy guns were a different issue entirely. The government did have smoothbores that could be converted, but not nearly enough to supply the needs of the Army, especially as the conflict wore on. There was really no choice but to purchase additional guns as field pieces were captured or destroyed. If smoothbores were truly obsolete, one would expect any purchases by this date to be for rifled cannon. But here is an order in 1863 for a smoothbore, and it is one of many.

It is true that the Rodman design did offer some improvements in manufacturing that lead to a more resilient gun. But it was still a smoothbore, limited in range and accuracy. By this date in the war, the reports from both the Army and Navy would have been telling a similar story. Ships with rifled guns could take down another ship armed with smoothbore cannon before the victim could even get close enough to fire a shot. On land the story was similar, and in practice an army with rifled cannon and sufficient ammunition enjoyed significant tactical advantages.

But there were also problems being documented in the many field reports he would have read as Chief of Ordnance, and not in small number. Field conditions during the Civil War were harsh and dirty. Keeping a gun clean, especially in the heat of battle, was difficult. And a dirty rifled cannon was far more prone to malfunction or misfire than a smoothbore subjected to similar conditions. To a soldier fighting to stay alive and win the day, an inferior gun that fires is better than a technologically superior gun that doesn't. At sea conditions were also harsh, and many commanders reported trouble keeping the rifled guns "hot" when it counted.

Looking at a purchase decision as a long-term investment, as any government official must, even more doubts would have emerged. Rifled weapons wear out faster than their smoothbore counterparts as the grooves that guide the projectile wear down from firing. When this happens, the gun can be re-rifled or decommissioned if re-rifling can't be safely executed. A comparative smoothbore under the same use would simply last longer, and with far less maintenance cost over that duration. And in fact, smoothbore cannons saw continued procurement and use into the 20th century, despite the availability of rifled alternatives. For an application like coastal defenses, a case could be made that the more reliable, servicable and generic smoothbore was good enough.

While there are some reports of 10-inch Rodman guns like the one purchased in this document being used during the Civil War, most notably at the siege of Sumter, most were ordered to protect the US in coastal forts like Alcatraz. And since this order was made by Ripley when he was responsible for coastal defenses, it is likely that that was always the intended destination for this gun. There is no way to know the final disposition of the gun purchased here, but there is a good chance it was still in service as the new century turned. Not a bad investment.

Ultimately, the order for this smoothbore was approved by his successor, George D. Ramsay. Ramsay was also a career officer who had served with distinction under Zachary Taylor during the Mexican War. He seems to have been appointed mainly for his ability to get along with other people. A personal friend of Lincoln, he possessed a reputation for a don't-rock-the-boat mentality. Indeed, during Ramsay's tenure, he largely maintained the program and policies that Ripley had laid down. Except for the breech-loaders Lincoln wanted. Those were ordered right away.

I was surprised to see such a rich story emerge from this relatively mundane document. The order of a smoothbore gun after a superior design already existed parallels more modern dilemmas with new technologies. Factors like reliability, existing user base and sunk costs all strike against the idea that every development in technology is an advance that obsoletes old tech as soon as it is realized. Many advances are partially or even mostly lateral, and there is a world where both technologies will exist for a time together. And some arguably represent a step backwards in important ways that may not be immediately obvious.

The people pushing new technologies often seem not to know or care about these considerations. To these people, newer is better, even when it isn't. Many of these people are quite smart – what they lack is not intelligence but wisdom and a healthy sense of caution. They come armed with promises, with a "vision" they’d say, and a knack for casting naysayers or even just people with questions to be a group of crusty, shortsighted curmudgeons - people too stupid to not see only the obvious benefits and nothing else. They are often great at sales, fantastic liars and have really nice teeth. The existence of these people justify the value of men like Ripley, even if they overstep the mark on caution at times.

History has been generally harsh towards James Wolfe Ripley, and he is invoked by some historians as an example of a shortsighted, miserly Luddite that cared more about money than the lives of his soldiers. But I would argue that his concerns were based in reality, and were valid and important. Giving the soldiers guns they couldn't use when it counted wouldn't help keep them alive. Examination reveals a scrupulous and competent administrator for whom the determination of what was actually "superior" was not a one dimensional question. He wasn't just equipping the army, he was also looking after public money and investments and trying to do the right thing for both the present and future.

While I do agree that Ripley erred on the wrong side of caution and frugality at times, ordering a smoothbore cannon for coastal defense at this late date was not one of them. Neither was his refusal to switch regular issue rifles to breech-loaders or deploy Gatling Guns to every regiment. These decisions were based in sound and sober reasoning that stands the test of time. I view his removal as Chief of Ordnance as an example of Abraham Lincoln sticking his nose and prerogative into matters he didn't fully understand and degenerating into a tyrant when he didn't get his way, both vices he indulged in fairly regularly.

The Rodman Gun's improvements may have come late in the day, but history confirms that smoothbores still had their place and that the purchase was sound. The video below has some good 360 degree footage of an example of the 10-inch Rodman Gun documented here.